Introduction: Securing Your Legacy – The Imperative of Wills and Trusts

Estate planning is a fundamental process that allows individuals to proactively designate who will receive their assets in the event of their death or incapacitation. This crucial undertaking extends beyond mere financial arrangements, encompassing critical decisions about healthcare and the guardianship of dependents, thereby ensuring a holistic approach to one’s future and the well-being of their family. It is a common misperception that estate planning is solely for the affluent; in reality, it is universally relevant, ensuring that all possessions, regardless of their perceived value, are distributed precisely according to an individual’s wishes.

The act of engaging in estate planning fundamentally involves a choice between proactive control and default outcomes. When an individual takes the initiative to plan their estate, they are actively asserting control over their legacy, ensuring that their unique values, relationships, and financial priorities are respected and implemented. This proactive approach prevents the state’s “one-size-fits-all” intestacy laws from dictating the distribution of assets, which might otherwise lead to unintended recipients or outcomes that do not align with the deceased’s personal preferences. By formalizing their wishes, individuals safeguard their personal autonomy and intent beyond their lifetime, preventing generic state statutes from overriding their specific desires.

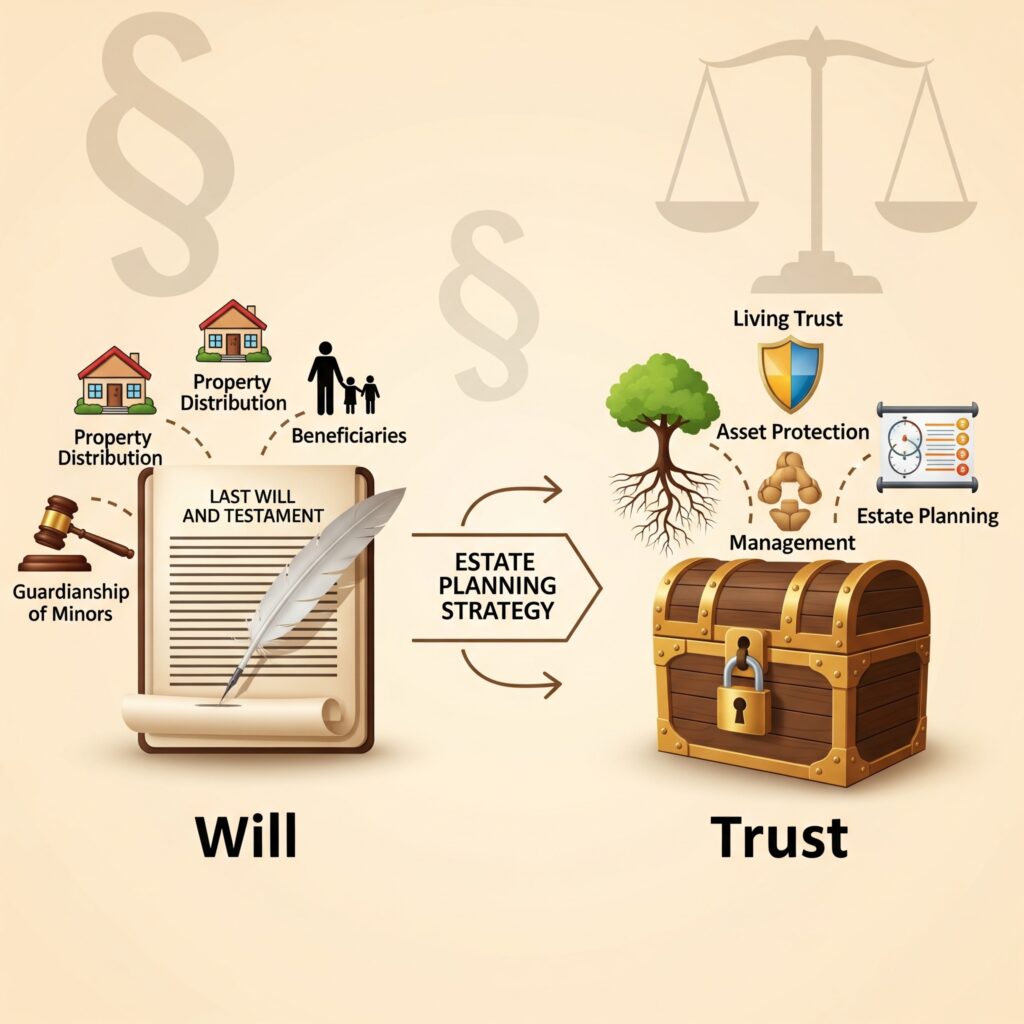

Within this comprehensive framework, wills and trusts stand as foundational legal instruments. A will primarily serves as a directive for property distribution after death. A trust, conversely, offers a more dynamic mechanism, capable of managing and distributing assets both during an individual’s lifetime and continuing seamlessly after their passing, often with the significant advantage of bypassing the probate process. Both documents are indispensable tools for comprehensive protection and efficient legacy transfer.

Understanding Your Will: Your Final Instructions for Asset Distribution and Guardianship

A will, formally known as a Last Will and Testament, is a legally binding document that articulates an individual’s precise wishes regarding the disposition of their property, assets, and the care of their minor children following their death. It represents the most straightforward and direct method to ensure that funds, personal effects, and real property are distributed exactly as intended. Crucially, a will’s directives only become effective upon the testator’s passing, initiating the process of carrying out their final instructions.

Key Benefits of a Will for Estate Management

A will offers several significant advantages, providing clarity and control over an individual’s estate.

- Directing Asset Distribution: A will grants the power to explicitly name beneficiaries—whether individuals or organizations—who will inherit specific assets, including monetary funds, real estate, and cherished personal possessions. This direct instruction ensures personal wishes are honored, preventing the default distribution dictated by state intestacy laws, which may not align with the deceased’s desires.

- Appointing Guardians for Minor Children: One of the most critical and exclusive functions of a will is the ability to legally designate a guardian for minor children. Without this explicit appointment, the decision falls to state courts, a process that can lead to emotionally taxing and prolonged custody battles, potentially resulting in a guardian being chosen who may not align with the parents’ values or preferences for their children’s upbringing.

- Naming an Executor: A will provides the authority to appoint an executor (also referred to as a personal administrator or personal representative), who will be entrusted with managing the estate after death. This individual is responsible for a multitude of tasks, including locating the will, settling debts, filing tax returns, managing financial accounts, and overseeing the precise distribution of the estate’s assets according to the will’s provisions. The selection of an executor is not merely a delegation of duties; it is the proactive establishment of a competent steward for one’s legacy. This prevents the state from appointing an unknown or potentially unqualified individual, a situation that could lead to delays, errors, unnecessary hardship, and significant financial uncertainty for the grieving family. The executor, therefore, acts as a crucial buffer, translating abstract wishes into concrete, legally compliant actions, thereby minimizing friction and safeguarding the family from potential legal and financial disarray during a highly vulnerable time.

- Peace of Mind and Reduced Family Stress: The act of creating a will offers invaluable peace of mind, knowing that one’s affairs are in order and that loved ones will be spared unnecessary stress and potential discord during an already difficult period of grief.

- Potential for Tax Reduction: While not its primary purpose, a thoughtfully drafted will can include provisions for bequests and donations to loved ones and charitable organizations, which may contribute to lowering potential estate taxes.

Common Types of Wills for Diverse Needs

The term “will” encompasses a spectrum of legal instruments, each tailored to satisfy varying individual needs and circumstances.

- Simple Wills: These are the most prevalent type, characterized by their straightforward nature. They are ideal for individuals with relatively few assets and uncomplicated estate plans, primarily used to outline basic asset distribution and to name guardians and executors. Their simplicity also makes them generally easy to draft and amend.

- Testamentary Trust Wills: This more complex will type establishes a trust after the testator’s death, as directed by the will’s terms. Assets are then transferred into this trust and managed by a designated trustee for the benefit of named beneficiaries, often with specific conditions, such as age-based distribution for minor children. This structure provides a higher degree of control over how and when beneficiaries receive their inheritance.

- Joint Wills: A single legal document executed by two individuals, most commonly married couples, to create a shared estate plan. While convenient, the terms of joint wills typically become irrevocable upon the death of the first spouse, which can present significant challenges if the surviving spouse’s wishes or circumstances change.

- Holographic Wills: These are wills written entirely by hand. While valid in some states without the need for witnesses, they must strictly adhere to specific requirements, such as being fully in the testator’s handwriting and properly signed and dated. They are often created in urgent or life-threatening situations.

- Living Wills: Distinct from traditional wills focused on asset distribution, living wills are advance medical directives. They outline preferences for end-of-life medical care and treatments should an individual become incapacitated and unable to communicate their wishes. They can also name a healthcare proxy to make medical decisions on one’s behalf.

- Pour-Over Wills: These wills are designed to work in conjunction with a living trust. Their purpose is to “catch” any assets that were not formally transferred into the trust during one’s lifetime and direct them into the trust upon death, ensuring that all assets are eventually managed under the trust’s provisions.

The diverse array of will types indicates that estate planning is not a static, one-time event but a dynamic process that must evolve with an individual’s life. A simple will might be sufficient at an early stage, particularly for younger individuals with fewer assets. However, as assets grow, family structures change (e.g., having children, remarriage, blended families), or specific long-term goals emerge, the need for more sophisticated instruments becomes apparent. For instance, a testamentary trust can provide structured disbursement for minor children, ensuring assets are protected until they reach a certain age or meet specific conditions. This adaptation of will types demonstrates the evolving nature of one’s estate plan, highlighting the importance of periodic review and modification to ensure continued alignment with changing life circumstances and objectives.

Understanding Your Trust: A Flexible Asset Management Tool for Probate Avoidance and Privacy

A trust is a legal structure that allows an individual (the grantor or trustor) to transfer assets to a trustee for management and distribution according to the grantor’s wishes. Unlike a will, which takes effect only upon death, a trust can be established and administered during the grantor’s lifetime and continues to manage and distribute assets long after their passing. Trusts are particularly valued for their ability to bypass the probate process, offering greater privacy and potentially faster access to assets for beneficiaries.

Key Benefits of a Trust for Comprehensive Estate Planning

Trusts offer several significant advantages, particularly for those with complex estates or specific long-term asset management goals.

- Avoiding Probate: One of the primary advantages of a trust is that assets held within it typically do not need to go through probate court. This simplifies and speeds up the distribution of assets to beneficiaries, allowing them to access their inheritances more easily and quickly. Bypassing probate also often results in reduced court fees and other associated costs.

- Maintaining Privacy: Unlike wills, which become public records during the probate process, trusts generally remain private. This confidentiality protects sensitive financial and personal details from public scrutiny, safeguarding the family’s legacy.

- Greater Control Over Asset Distribution: Trusts offer a high degree of flexibility and control over how and when assets are distributed. Grantors can include specific instructions for conditional distributions, such as spreading payments over time, releasing funds at certain ages, or requiring beneficiaries to meet specific milestones (e.g., college graduation). This level of control is particularly beneficial for managing inheritances for minor children, individuals with special needs, or beneficiaries who may not be adept at financial management.

- Asset Protection: Properly structured trusts can help safeguard assets from creditors, lawsuits, and even divorce proceedings involving beneficiaries. For irrevocable trusts, assets are transferred out of the grantor’s name, potentially placing them beyond the reach of personal judgments. This enables a level of granular control and protection, ensuring that the legacy remains intact and serves its intended purpose without being jeopardized by external claims.

- Incapacity Management: Trusts can be designed to provide for seamless management of assets if the grantor becomes incapacitated due to illness or injury. A successor trustee can step in to manage the trust assets without the need for court intervention, ensuring financial affairs continue uninterrupted.

- Minimizing Taxes: Certain types of trusts can be strategically used to reduce estate, gift, or income taxes. Irrevocable trusts, for instance, can remove assets from the grantor’s taxable estate, potentially decreasing tax liability, especially for large estates.

Common Types of Trusts for Specific Estate Planning Goals

Trusts come in various forms, each designed to address specific estate planning needs and objectives. The two basic structures are revocable and irrevocable trusts.

- Revocable Living Trusts: Also known as inter vivos trusts, these are established during the grantor’s lifetime and can be altered or revoked at any time by the grantor. They allow the grantor to maintain control over their assets while alive and are primarily used to avoid probate and provide for incapacity management. Upon the grantor’s death, a revocable trust typically becomes irrevocable.

- Irrevocable Trusts: Once established, an irrevocable trust generally cannot be modified or dissolved by the grantor without the consent of the beneficiary or a court order. The grantor relinquishes ownership and control over the assets transferred into an irrevocable trust. This type of trust is often preferred when the primary goal is asset protection from creditors, lawsuits, or significant tax reduction, as the assets are removed from the grantor’s taxable estate.

- Testamentary Trusts: As previously discussed, these trusts are created through a will and become effective only upon the grantor’s death and after the will has gone through probate. While they offer control over asset distribution, they do not avoid probate.

- Special Needs Trusts (SNTs): These are specifically designed to provide financial support for individuals with disabilities without jeopardizing their eligibility for government benefits such as Medicaid or Supplemental Security Income (SSI). SNTs ensure that inheritances supplement, rather than replace, essential public assistance.

- Charitable Trusts: These trusts involve gifting assets to a qualified charitable organization while potentially providing benefits to the grantor or other non-charitable beneficiaries. Examples include Charitable Remainder Trusts (CRTs) and Charitable Lead Trusts (CLTs), which can offer income streams and tax deductions.

- Life Insurance Trusts (ILITs): An irrevocable trust designed to own a life insurance policy, effectively removing the policy proceeds from the insured’s taxable estate and providing liquidity to heirs upon death.

- Generation-Skipping Trusts (GSTs): These trusts are structured to transfer wealth to grandchildren or later generations, bypassing the children’s generation to potentially avoid estate taxes at each successive generation.

Consequences of Dying Without a Will or Trust (Intestacy): Understanding the Risks

Failing to establish a will or trust can have profound and often undesirable consequences for an individual’s estate and their loved ones. When someone dies without valid estate planning documents, their estate enters a state known as intestacy. In such cases, state law dictates how assets are distributed, which may not align with the deceased’s personal preferences or their family’s needs.

State-Determined Asset Distribution and Probate Challenges

Without a will or trust, the distribution of assets falls under the jurisdiction of state intestacy laws, which outline a predetermined order of inheritance for surviving relatives. This typically prioritizes spouses and children, followed by parents, siblings, and more distant relatives if no closer kin exist. Unmarried partners, for example, typically receive nothing under intestacy laws, regardless of the depth of their relationship. If no surviving family members are found, the assets may “escheat” or go to the state government, completely disregarding any personal wishes for friends, community, or charity.

Furthermore, dying intestate means the estate must go through the probate process. This court-supervised procedure involves identifying and valuing the deceased’s assets, notifying creditors, paying off debts and taxes, and finally distributing the remaining property to the rightful heirs as determined by state law. The court will also appoint an administrator to manage the estate, a role that the deceased would have chosen themselves had a will been in place.

Financial and Emotional Impact on Loved Ones Due to Intestacy

The absence of a will or trust can lead to significant financial and emotional burdens for surviving family members.

- Lengthy and Costly Probate: Probate without a will can be a protracted and expensive process. It can take months or even years to resolve, especially for complex estates or if disputes arise among potential heirs. The accumulated fees, including court costs, administrator fees, and appraisal fees, can significantly reduce the value of the estate, leaving less for the intended beneficiaries.

- Public Nature of Proceedings: Probate proceedings are a matter of public record. This means sensitive information about the deceased’s assets, debts, and beneficiaries becomes accessible to anyone, potentially inviting unwanted scrutiny or even fraudulent claims.

- Lack of Guardianship Designation: For parents of minor children, dying without a will creates a critical issue: guardianship. Without a will, the court will decide who will care for the children, which can result in lengthy custody battles or the appointment of a guardian who may not have been the parents’ first choice or who may not align with their values.

- Family Disputes and Discord: Intestacy laws can lead to significant family conflicts and disagreements over asset distribution. When clear instructions are absent, family members may argue over who has the “moral” or “legal” claim to assets, straining relationships during an already difficult grieving period.

- Financial Uncertainty and Missed Opportunities: Assets may be frozen until the probate court finalizes distribution, potentially leaving loved ones unable to access needed funds for months or years. Furthermore, the opportunity to implement tax-efficient strategies is lost, meaning a larger portion of the estate could go to taxes rather than to beneficiaries. Dying intestate also means losing the chance to leave a lasting legacy through charitable contributions, specific heirlooms, or educational trusts.

Establishing Your Estate Plan: Process and Legal Requirements for Wills and Trusts

Creating a legally sound will or trust involves specific steps and adherence to legal requirements, ensuring that the documents are enforceable and accurately reflect one’s intentions.

Process for Creating a Will: Step-by-Step Guide

The process for creating a will involves several key steps to ensure it is legally binding and accurately reflects one’s wishes.

- Understanding the Basics of a Will: A will is a crucial legal document that outlines how assets and property will be distributed after death. It ensures intentions are carried out and helps prevent potential legal conflicts and costs.

- Legal Requirements for a Valid Will: To be legally valid, a will must meet specific criteria :

- Age and Mental Capacity: The testator must be at least 18 years old and possess sound mental capacity, meaning they are fully aware of their property, beneficiaries, and how assets are being distributed.

- In Writing and Signed: The will must be in writing and signed by the testator, or by someone else at their direction and in their presence.

- Witnesses: The will must be signed by at least two individuals who are not beneficiaries, and they must sign in the testator’s presence.

- Notarization (Optional but Recommended): While not always required (except in Louisiana), notarization can help ensure the will’s validity, especially if it might be used in different states, making it “self-proving”.

- Preparing to Write the Will (Documentation): Before drafting, it is essential to gather necessary information and documents :

- Listing Assets and Personal Property: A comprehensive list of all assets (real estate, vehicles, heirlooms, financial accounts) ensures everything is identified and distributed as wished.

- Identifying Beneficiaries: Clearly identify all individuals or organizations designated to receive property, using full legal names and specifying their relationship.

- Information for Executor/Guardians: Personal information for chosen executors and guardians, including contact details and any relevant qualifications.

- Writing the Will: Essential Components: The will should include :

- Appointing an Executor: Naming a trustworthy and responsible individual to manage the estate, settle debts, and distribute assets.

- Naming Guardians for Minor Children: Designating legal guardians for children in case of the parents’ passing.

- Distributing Assets and Personal Property: Specific instructions on who receives which assets, with detailed descriptions to prevent confusion.

- Making the Will Legally Binding: Ensure proper witnessing and signing, and consider notarization.

- Storing and Communicating the Will: Store the original document securely (e.g., fireproof box, bank safe deposit box) and inform the executor, guardians, and beneficiaries of its location and their roles.

- Updating the Will: Regularly review and update the will after major life events (marriage, divorce, birth/death of a child, significant financial changes). Updates can be made by creating a new will or adding a codicil.

Process for Creating a Trust: Key Steps and Funding

Establishing a trust is generally more complex than creating a will, often requiring legal expertise.

- Decide on Assets to Include: Determine which assets (cash, real estate, stocks, investments, business interests) will be placed into the trust.

- Identify Beneficiaries: Clearly name the individuals or organizations who will benefit from the trust.

- Determine Trust Rules and Purpose: Define the specific purpose of the trust and set parameters for how and when funds or assets should be distributed (e.g., age-based distributions, for college expenses).

- Select a Trustee: Choose a trustworthy and responsible individual or institution (e.g., a bank) to manage and distribute the trust assets according to the grantor’s wishes. Naming a successor trustee is crucial.

- Draft the Trust Document with an Attorney: This is a critical step, as trust documents must comply with state laws and accurately reflect complex intentions. The document should clearly state the grantor’s intent, identify the subject matter (assets), and name the beneficiaries.

- Sign and Notarize: The trust document typically requires notarized signatures from the grantor, trustee(s), and potentially successor trustee(s) to confirm legality and voluntary agreement.

- Fund the Trust: A trust becomes valid only after assets are formally transferred into it. This involves changing titles for real estate, re-registering bank and investment accounts, and assigning ownership rights for other property to the trust. A trust cannot provide benefits if it is empty.

- Store and Keep Updated: Store the document securely and review it regularly, especially after major life changes, to ensure it remains aligned with current wishes and circumstances.

Legal Requirements for a Valid Trust Document

For a trust to be properly constituted and legally enforceable, it must satisfy several conditions, often referred to as the “three certainties” (certainty of intention, subject matter, and object) in some legal traditions, alongside other formal requirements.

- Mental Capacity of Grantor: The individual establishing the trust must have the mental capacity to understand the implications of their actions.

- Clear Intent to Create a Trust: The grantor must clearly demonstrate an intention to create a trust. The specific word “trust” is not always necessary, as equity prioritizes intent over form.

- Identifiable Trust Property (Certainty of Subject Matter): The assets or property subject to the trust must be clearly identified and certain at the moment of creation. It must also be clear what part or share of the property each beneficiary is entitled to.

- Ascertainable Beneficiaries (Certainty of Object): The legal document must include named beneficiaries who will receive the assets. A trust must be for ascertainable beneficiaries, as courts need to be able to enforce the trust in their favor.

- Named Trustee and Defined Duties: There must be a designated trustee responsible for managing the assets, and their duties and rights must be clearly outlined.

- Valid Execution and Funding: The trust must be executed in a manner that complies with state law, often requiring notarized signatures. Crucially, the trust must be “funded” by transferring assets into it for it to be effective.

Wills vs. Trusts: A Comparative Overview for Estate Planning Decisions

While both wills and trusts are integral components of estate planning, they serve distinct purposes and offer different advantages. Understanding these differences is key to determining the most suitable strategy for an individual’s unique circumstances.

| Feature | Will | Trust |

| Takes Effect | Upon death | Upon funding (can be during lifetime) |

| Probate | Generally required | Generally avoids probate |

| Privacy | Public record during probate | Generally private |

| Asset Control | Directs distribution after death; limited control post-distribution | Manages assets during life and after death; offers granular control (e.g., conditional distributions) |

| Incapacity Planning | Does not plan for incapacity directly (requires separate Power of Attorney) | Can manage assets if grantor becomes incapacitated |

| Guardianship for Minors | Can appoint | Cannot directly appoint (requires a will) |

| Cost & Complexity | Generally simpler and less expensive to set up | More complex and costly to set up and maintain |

| Asset Protection | Limited; assets generally distributed outright to beneficiaries | Can protect assets from creditors, lawsuits, and irresponsible spending by beneficiaries (especially irrevocable trusts) |

| Tax Benefits | Can help reduce estate taxes through bequests | Certain types can significantly reduce estate, gift, or income taxes |

| Flexibility | Easily updated via codicil or new will | Revocable trusts are flexible; irrevocable trusts are generally unchangeable |

| Typical Use Cases | Simpler estates, appointing guardians, basic asset distribution | Complex estates, high net worth, privacy concerns, asset protection, conditional distributions, special needs planning |

When to Use a Will for Basic Estate Needs

A will is often the most appropriate choice for individuals with relatively straightforward estates and family structures. It is particularly indispensable for parents of minor children, as it is the sole legal instrument that allows for the appointment of a guardian. For those with fewer assets or who prioritize simplicity and lower upfront costs, a basic will can effectively ensure asset distribution according to their wishes and name an executor to oversee the process. Wills are also easily updated to reflect life changes, offering flexibility as circumstances evolve.

When to Use a Trust for Advanced Asset Management

Trusts are generally recommended for more complex estates or when specific objectives beyond basic asset distribution are desired. They are particularly advantageous for individuals who wish to avoid the public and potentially lengthy probate process, maintain privacy regarding their financial affairs, or exert greater control over how and when their assets are distributed to beneficiaries. Trusts are also invaluable for asset protection, minimizing taxes, and providing for incapacity management. For blended families or those with beneficiaries who have special needs or require structured financial management, a trust offers tailored solutions that a will cannot.

The Power of Synergy: Combining Wills and Trusts for Comprehensive Protection

The decision between a will and a trust is not necessarily an either/or proposition. In many instances, the most robust and comprehensive estate plan involves combining both a will and a trust. This strategic synergy allows individuals to leverage the unique strengths of each document, creating a dual framework that covers all aspects of an estate and prepares for various contingencies.

The strategic synergy of wills and trusts is a powerful approach to estate planning. It acknowledges that while a will is essential for certain critical functions, such as appointing guardians for minor children, it is limited in its ability to manage assets during life, ensure privacy, or avoid probate. Conversely, a trust excels in these areas but cannot designate guardianship. The combined use of these documents creates a comprehensive and resilient plan. A will can serve as a “pour-over” mechanism, directing any assets not explicitly transferred into the trust during one’s lifetime to be moved into it upon death. This coordination eliminates potential gaps that could lead to confusion or unintended consequences, ensuring that all assets are eventually managed according to the trust’s provisions. This partnership is particularly valuable when addressing the needs of loved ones, as a will provides for dependents and personal items, while a trust offers financial security through structured asset management. The overarching benefit is a significant reduction in the likelihood of disputes among heirs and a streamlined, more efficient process for wealth transfer, ultimately bringing greater assurance that one’s intentions will be honored.

Benefits of a Combined Estate Planning Strategy

- Comprehensive Coverage: A combined approach ensures that all assets are accounted for. While a trust manages larger or more complex assets (especially those intended to avoid probate), the will can address any property not included in the trust or acquired after the trust was established, acting as a “pour-over” will to direct these assets into the trust.

- Guardianship and Asset Management: The will fulfills the critical role of naming guardians for minor children, a function a trust cannot perform. Simultaneously, the trust provides structured asset management, offering financial security and control over distributions for beneficiaries, especially minors or those with special needs.

- Streamlined Probate and Privacy: Assets held in a trust bypass probate, offering privacy and faster distribution. The will, while potentially going through probate for non-trust assets, can still simplify the process by providing clear instructions and appointing an executor, thereby reducing delays and disputes.

- Incapacity Planning: Beyond death, estate planning also addresses potential incapacity. A trust can manage finances if an individual becomes unable to make decisions due to illness or injury. A will can be paired with durable and medical powers of attorney to cover healthcare and legal matters, ensuring comprehensive care and management during a period of incapacitation.

- Reduced Disputes and Stress: By providing clear communication and legal safeguards, a combined strategy minimizes ambiguity and helps prevent disputes among family members, reducing legal and emotional hurdles during difficult times.

Importance of Professional Guidance in Estate Planning

Given the complexities and nuances of estate planning, consulting with qualified legal professionals is highly advisable. While online resources and DIY templates exist, they may not be suitable for all situations, particularly for complex estates or those with unique family dynamics. An experienced estate planning attorney can interpret the myriad of laws, provide customized advice, assist with drafting legally sound documents, guide on minimizing taxes, and ensure that assets passing outside of a will or trust are properly handled. This professional guidance can prevent costly litigation, delays, and unintended outcomes, ultimately providing significant peace of mind.

Conclusion: Why Wills and Trusts are Essential for Your Legacy

The decision to establish a will, a trust, or a combination of both is a critical component of responsible financial and personal planning. These legal instruments are not luxuries reserved for the wealthy; they are indispensable tools that empower individuals to exert control over their legacy, protect their loved ones, and ensure their final wishes are honored. Without these essential documents, an estate is subject to state intestacy laws and the often lengthy, costly, and public probate process, potentially leading to unintended asset distribution, family disputes, and significant emotional and financial strain on grieving relatives.

A will provides the fundamental ability to direct asset distribution and, uniquely, to appoint guardians for minor children. Trusts, meanwhile, offer unparalleled flexibility, privacy, and control over asset management, allowing for conditional distributions and robust asset protection, often bypassing probate entirely. The most comprehensive approach often involves a synergistic combination of both a will and a trust, creating a resilient framework that addresses all aspects of an estate, from guardianship to complex asset management and incapacity planning.

Ultimately, proactive estate planning is an investment in peace of mind and a profound act of care for one’s family. It safeguards assets, minimizes legal complexities, and ensures that an individual’s unique values and intentions continue to shape their legacy long after they are gone. Seeking professional legal guidance is paramount to navigate these complexities and craft an estate plan that is tailored to specific needs and objectives, providing enduring security for future generations.